Post Traumatic Growth - the psychology behind Thrive

/Over the last few months we've been sharing blogs from both the Cast and Creative Team of Thrive. But we've saved one of the most important contributors until last. Thrive's Psychology Consultant, Dr Roger Bretherton tells us about the science behind the show and how that can help us find hope in the hardest of times. Here's the science bit...

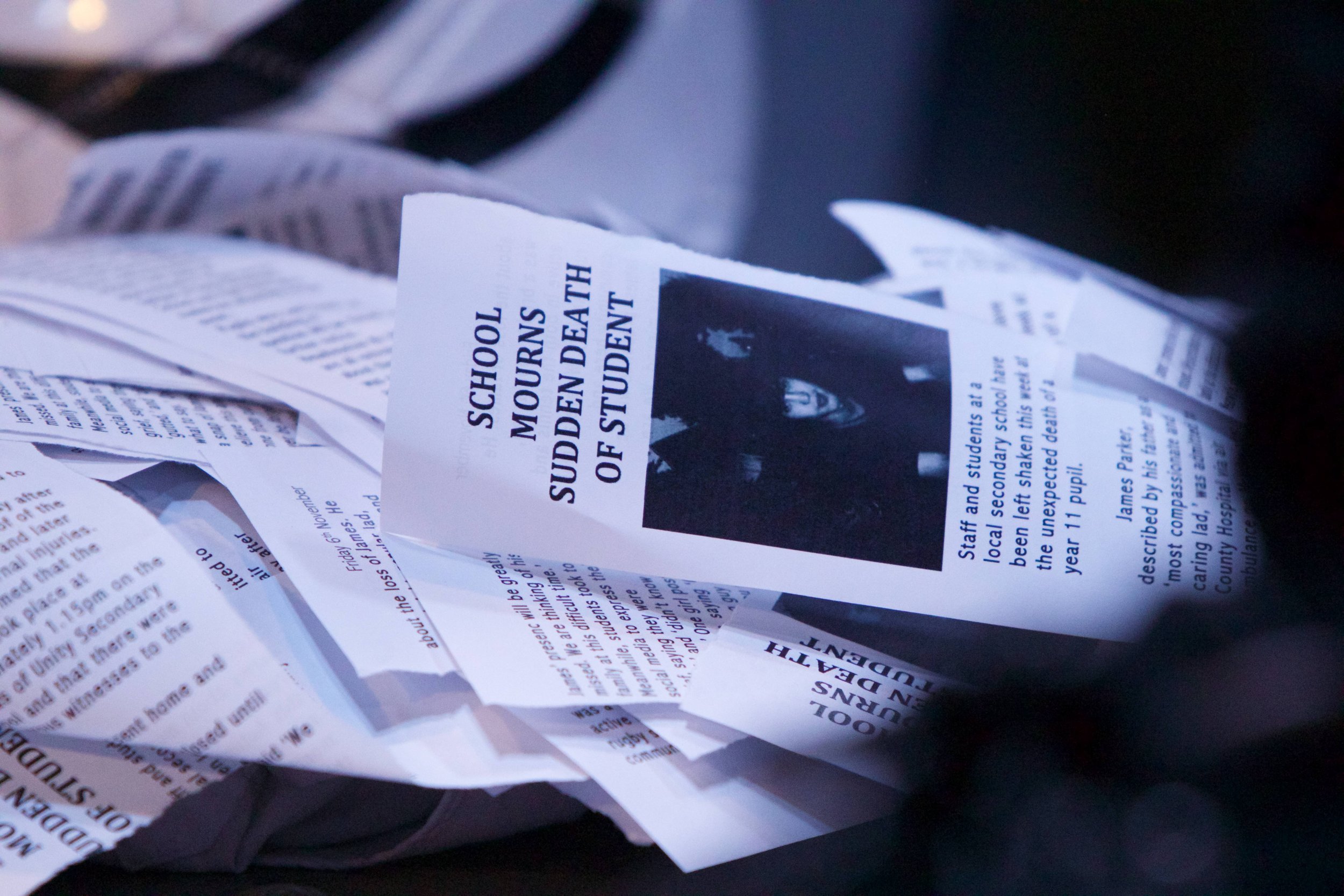

I think it would be fair to say that most of us live our lives hoping that bad things won't happen to us. Sickness, death, abuse, injury, mental illness- we hope they'll stay away from us and the people we love most. But it's not realistic. Sooner or later the dark side of life makes its presence felt. Someone we love dies unexpectedly, or we get ill, or we suffer at the hands of someone who sets out to harm us. Life isn’t always easy and there are no guarantees. For the last twenty years or so, psychologists have studied the incredible strength of character that can emerge in a minority of people when they face painful events. Twenty years of research tells us that these events needn’t destroy us – in some cases, they can make us stronger. Some people become wiser, others kinder, others more connected. Pain develops people in all kinds of ways. This field of research is called Post Traumatic Growth, and forms the basis of the psychology surrounding the characters in Thrive.

When I first sat down with Toby in Spring 2015, we had no idea that Thrive would become the story that it did. Zest’s previous show had been a light, high energy piece using silent disco technology, something that we also considered for Thrive in the very beginning, but in the end we decided it wasn’t necessary to enhance what we were trying to say. We started talking about how different people cope in different ways, some avoid, some problem-solve, some process; this naturally led us to having three different characters that embody some of those coping tactics.

I remember the first day of rehearsals I was really nervous and excited to be on board. I have always loved theatre, so the chance to work on a piece that so perfectly merged it with psychology was a dream gig (my colleagues were really jealous!). However, I do remember thinking that Toby was slightly nuts to start with no raw material and just me talking to the actors for two days! Having said that, this I believe now is one of the strengths of Thrive; that all that early work makes it firmly rooted in academic research and knowledge. It is not a glib or naive story, but something based on solid foundations. I had done a bit of TV consultancy on mental health before, but never to this extent, so I felt a real responsibility to not make it crap or like the many stereotypical portrayals of mental health we see so often. It’s a really difficult balance, as you need to give enough signposts to an audience so that they understand what you are trying to tell them, but also need to be subtle enough to let them reach some conclusions on their own. Thrive is so full of layers and subtlety and I think the audience really see and appreciate that.

One of the most interesting parts of the rehearsal process was after the actors had begun to create different characters. I sat them down one at a time and essentially gave them therapy. This is something I do a lot in my everyday work so am quite confident in, but the actors gave me a real run for my money! One of the characters, Ollie, had a lot of anger and another, Ashleigh, was resisting any interaction, so it brought up some professional anxiety for me, and I had to utilise all the skills I had learnt to make the session productive. It reminded me that sometimes a good therapy session is just letting the person be where they are in their journey and roll with their feelings. The therapy scenes you see in Thrive came out of these early interactions. It was a bit strange giving therapy to the characters, but even in the early stages they felt so honest and real that I could really empathise with their situations and the strong emotions they brought up.

Another important thing to me during the process was that we didn’t trivialise the trauma that these young people have been through, or give a clichéd happy ending. Trauma affects us all in different ways; what is traumatic for one person may not be for another, and, when you are dealing with such sensitive material and taking your audience on such an emotional journey, you have a duty of care to your audience as they may have had similar life experiences. Not everyone who experiences trauma will grow from it. Trauma can leave us thriving, healing or surviving.

There were points throughout the Thrive process where I wondered how accurately we had portrayed what we wanted to say. Then, during an early showing in Lincoln, a young girl approached me after the show and thanked me. She explained that she had lost her best friend the year before and that we had gotten the emotion of the experience bang on with Thrive. For me, I found that really comforting and a real testament to the team’s hard work.

If there’s one thing I would want people to take from Thrive, it’s a sense of hope and peace. Although the audience are put through a chaotic and disruptive experience, ultimately by the end, there is hope for the future. We aren’t saying that life is going to be easy or pain free, of course there will be obstacles, big and small. Thrive is therefore about all of us as we navigate our way through the hazards of life. It suggests that in the face of pain we can become better not just bitter, we can grow not just shrink, we can thrive not just decline. Our greatest challenges need not break us, they can make us.